I'm working on fleshing out the interiors for this addition renovation project here in Vermont.

G-Jan-4 from Robert Swinburne on Vimeo.

I'm working on fleshing out the interiors for this addition renovation project here in Vermont.

G-Jan-4 from Robert Swinburne on Vimeo.

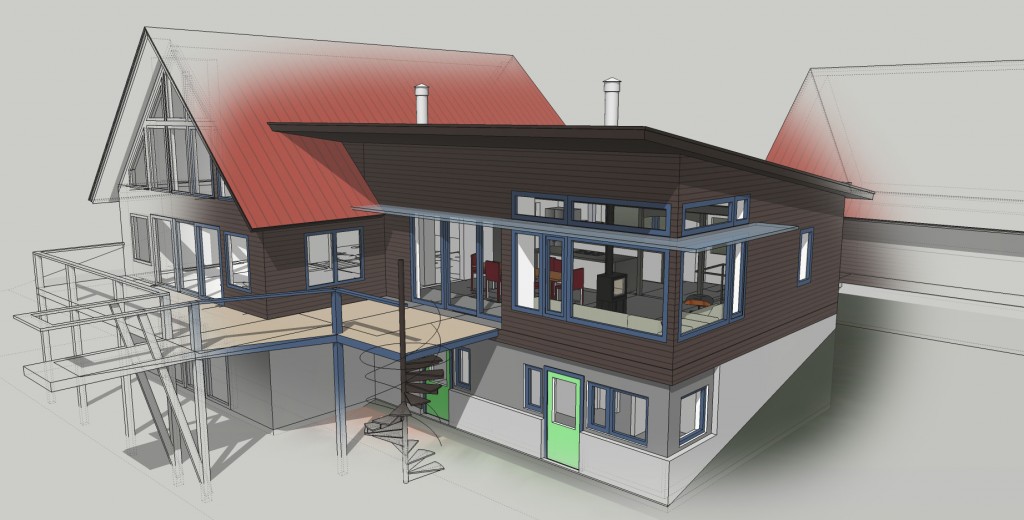

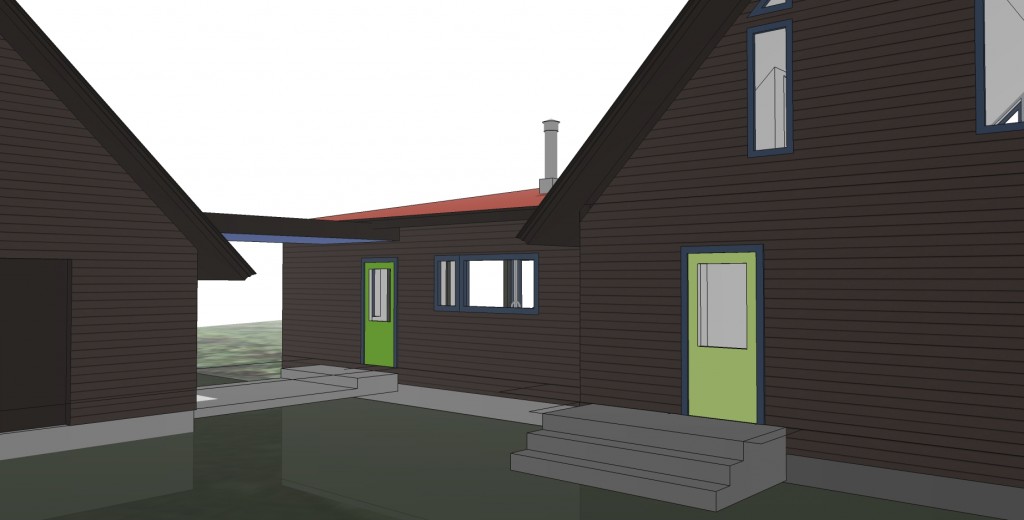

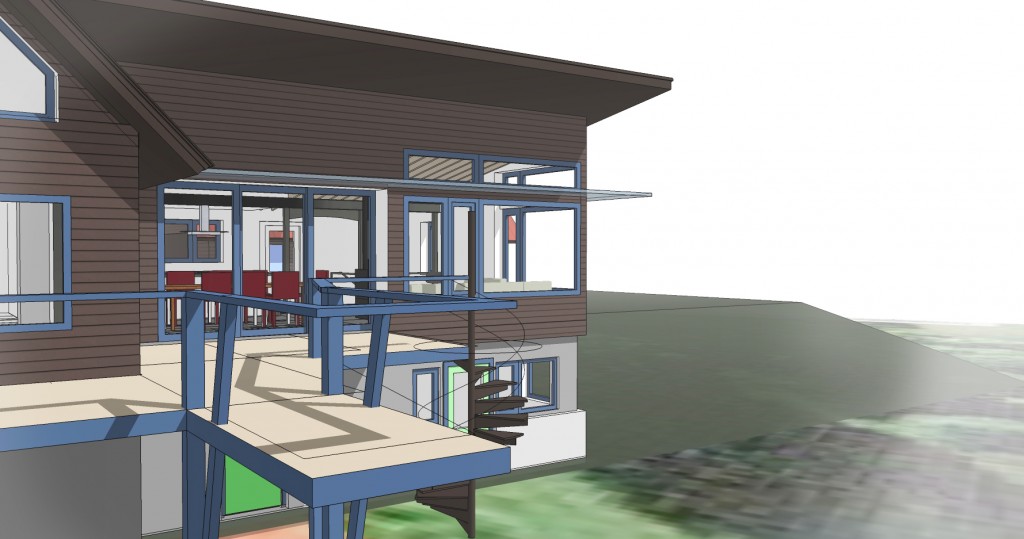

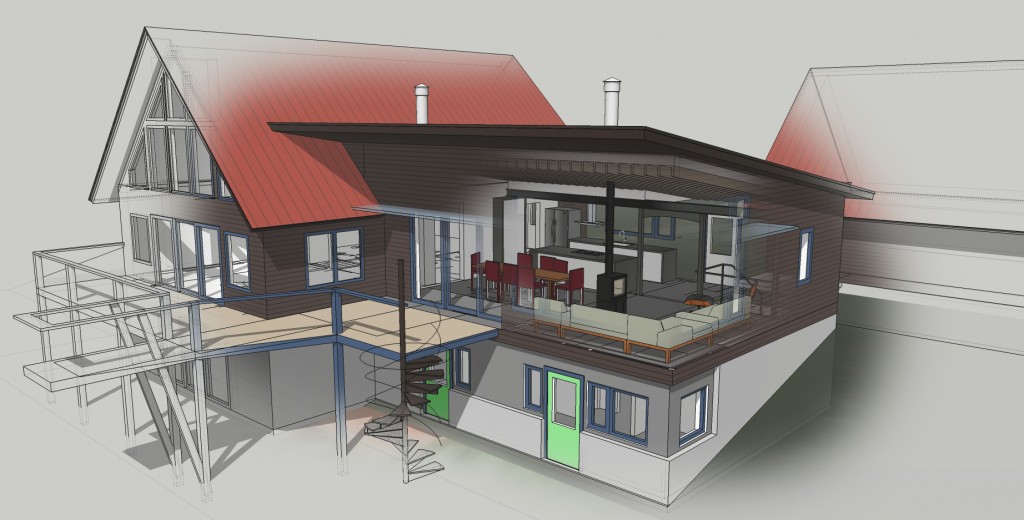

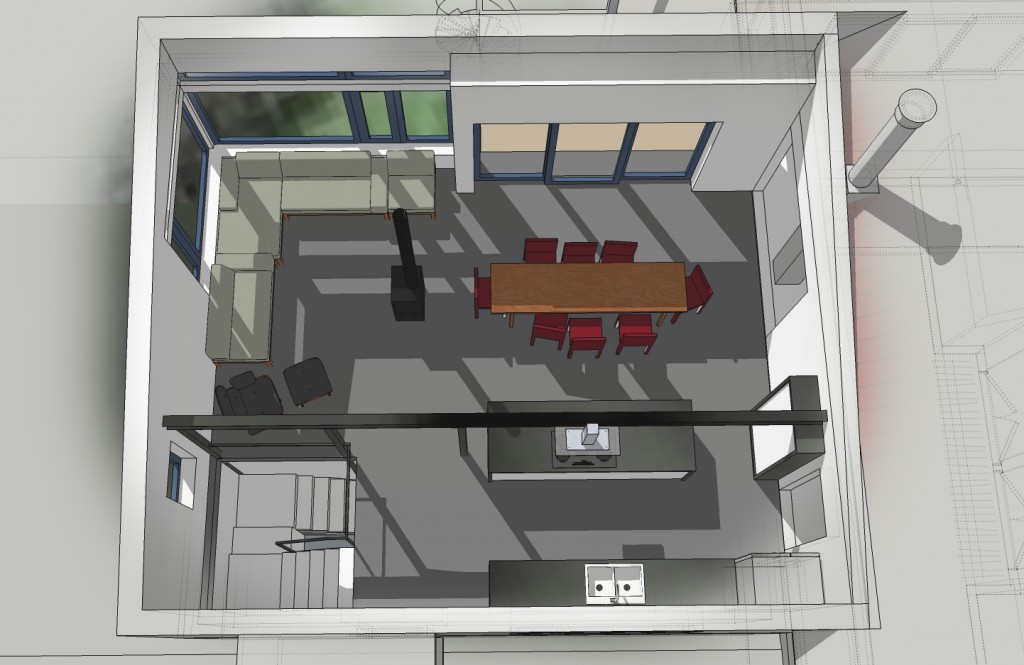

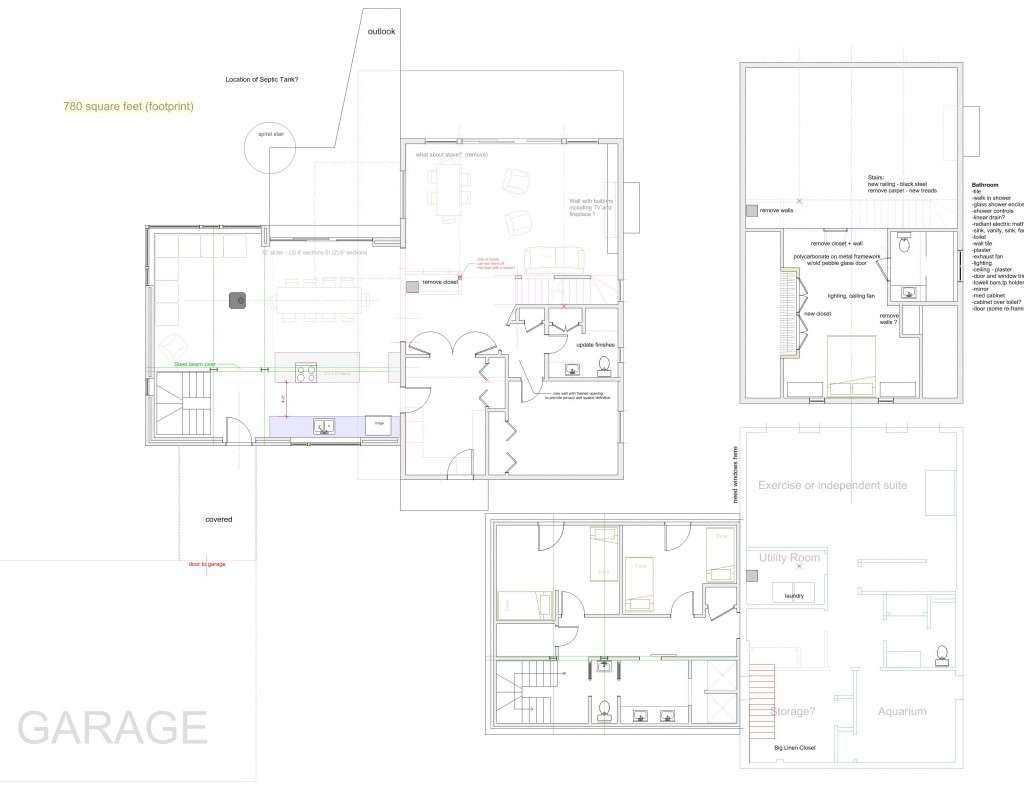

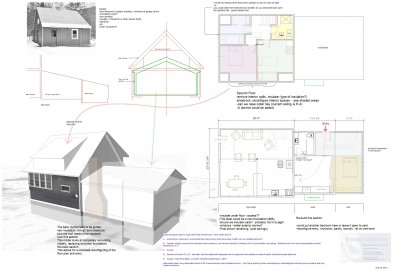

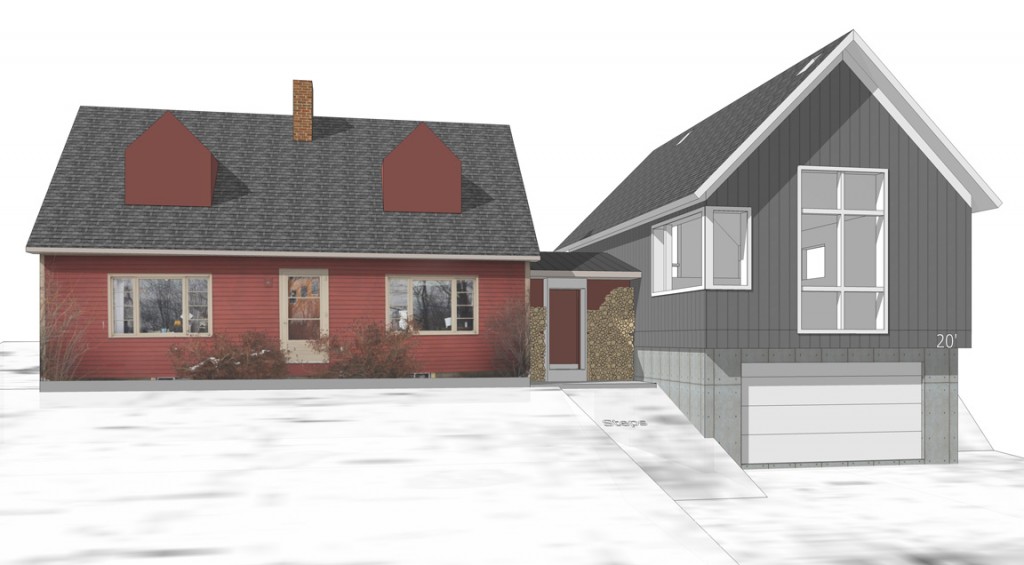

One of the projects I'm working on is an addition to and renovations of a ski home in Vermont. The main house is well built and and other than a maroon and pink bathroom and rather 80's finishes, we are not doing anything too major to it. We are locating a family room addition between the existing house and garage which will provide a much nicer kitchen and living area plus additional bunkrooms and a multi-user bath on the basement level. I'm sticking with the dark clapboard and red standing seam roof of the existing as I think it provides a nice base for some fun things to happen with color at the doors and windows.

We are locating a family room addition between the existing house and garage which will provide a much nicer kitchen and living area plus additional bunkrooms and a multi-user bath on the basement level. I'm sticking with the dark clapboard and red standing seam roof of the existing as I think it provides a nice base for some fun things to happen with color at the doors and windows.

I am using big windows, wood, steel etc to create a warm, modern and relaxed space for lots of people to be in.

I am using big windows, wood, steel etc to create a warm, modern and relaxed space for lots of people to be in.

Here is the current plan:

Here is the current plan:

and I put together a few videos of the sketchup model

and I put together a few videos of the sketchup model

A House for Slow LivingThe original concept came to me in a dream (yes – I dream architecturally) I think the dream may have been generated by this image which has been on my bulletin board fora few years:

The original sketch was called “a house for food”

The original sketch was called “a house for food”

The core concept was centered around the growing, preparation and consumption of food which lends itself to the idea of gatherings of family and friends and leads to the notion of how to live in a close relationship to the local environment. From my own experience I drew upon the old fashioned ideas of hunkering down by the fire on a cold winter evening, opening the house up to the sounds, smells and breezes of a summer day, “putting food by” and making routine preparations for winter in the Autumn, starting seedlings on a windowsill in the spring, caring for children or elders. Also, how can we appreciate the beauty of the winter landscape and light without feeling overcome by it. This is a common issue in the Northeast. Where do you sit to watch a thunderstorm rolling in or to watch the snow fall? Music! – not just acoustics but around here, everybody is also a musician. How does that fit into our daily lives? Much inspiration is to be found in images and stories depicting rural life from previous times in Europe and America. I am drawn to the imagery of hard working English country houses where the real life of the house centers between the kitchen and the door stoop leading directly to the working yard and gardens. Think: Peter Rabbit in Mr. McGregor’s Garden by Beatrix Potter with a potting shed, cold frames and lots of cabbages. I am fascinated by early New England farms and town dwellings and how lives were played out in them. Not the big events but the little, day to day, season to season routines. Light and fresh air are celebrated and sought after and even, perhaps, taken for granted in an age before television and telephones. Materials are worn but durable, practical and show their age and history and that is where their beauty lies.

The Building Science aspect of design and detailing that we are all so immersed in lately addresses the idea of being able to lock the door and walk away for a month in the winter and not worry about much of anything. The neighbor has the key and will water the plants. Building Science addresses being what we are calling “net zero” so you are not storing and burning fossil fuel on site and paying for it as well. Building Science addresses the notion of simplicity – who needs a heating system that could go on the fritz and bust your pipes and freeze all your house plants so when your neighbor comes over to water the house plants, he finds an awful mess and has to call you in some recently devastated country where you are doing relief work. Building Science allows you to return in March to a house filled with fresh air and no mildew. (building science can’t help with what you left in the fridge) Building Science can free you from many previously taken for granted maintenance issues and expenses such as painting and periodic repair, maintenance and replacement of the mechanical parts of the house because now you have fewer and simpler systems.

How then, to marry my heady and romantic thoughts with the physics of modern building science? How do I pack all of this sensuality and feeling into a house that celebrates the process of living this chosen life rather than reminding one of the potentially inherent drudgery? Since these ideas are very personal to me, it isn’t very difficult to make a series of design moves and decisions that bring me pretty close. I have been moving in this direction for much of my life. I am often “pretty close” but getting to that higher level is tricky and elusive. I’m not there yet with this design but it’s still early….

In this design, I'm trying to balance small and simple with a richness of space that goes far beyond light and shadow, a good floor plan and simplicity of form and add my own interpretation of what it can mean to live in Vermont and lead a life integrated with the climate and culture of the place. I'm drawing heavily on history and my own sense of aesthetics as well as all my cumulative observations and experience.

Dang! Maybe I should tear down my own house and build something like this!

For those interested in the Slow Living Movement, Brattleboro has a Slow Living Summit coming up in June associated with the Strolling of the Heiffers parade and festival.

Bob has been asking me for some time to write a guest blog entry and since he has happily been to busy of late to write much himself, I thought this was a good time to finally make good on my promise to do so. Last year, I had a visit with an old friend who had recently moved back to the area. I hadn't seen her for a while, and it was the first time I'd seen her new house since it was just a partially-erected timber frame. It was lovely to see my friend after such a long gap, and also fodder for pondering and a blog entry.

The house was nice—open, tasteful, bright and spacious (huge by our standards) and it fulfilled their goal of functioning as somewhat of a community gathering place as well as a home. For example, they were holding a weekly meditation group in a specially designed meditation/yoga area. But I couldn't help thinking that if Bob had designed it, it could have met their needs so much more simply, elegantly and with much less square footage.

Of course I said nothing (how can you say something like that and what would be the point?) as I had said nothing during their design process. It seems rather self-serving to say to a friend who's designing their own dream house, “you know, you should really consider hiring my husband.”

But what I learned next makes me question whether that was really the best approach. When somebody builds a house, you expect them to be excited, even jubilant with the result. Instead, my friend told me that she felt like she had PTSD. There wasn't a single corner of the house she could look at without dredging up the stressful arguments with contractors over that bit of construction. She wished she could be rid of the house, but they were sunk in it for so much more than market value, that wasn't an option.

The biggest mistake they had made was to get sweet-talked by the GC into inadequate planning and problem-solving. One thing Bob stresses to all his clients is how much easier it is and how much cheaper it is to work out problems on paper. My friend believed her charismatic contractor that they could figure it all out as they went. What she figured out is that it's very expensive to pay for an entire crew to stand around and wait while hasty compromises are made.

I could go on, but you get the point. My friend's unfortunate house-building experience is a classic example of why it pays to pay for someone good to be on your side. Of course, that's no guarantee of satisfaction either, I suppose. I'm thinking of some clients who fired Bob a few years back after he showed them a rendering of what the addition floor plan they loved would look like in elevation. Not at all what they'd expected. You'd think they might have been appreciative to discover that after a few hours of design time rather than mid-construction. No accounting for people. It's now once again been a while since I caught up with that friend. I hope she's come to peace with her process by now, and that she's enjoying her home. And if another friend embarks on the process of building a home? I wonder if I'll serve them by being self-serving. I'll probably just give them some generic advice about working all the kinks out that they can on paper, and leave it at that. After all, my friends all know I'm married to an architect.

HA! This happens a lot. I just got a call from a contractor who wanted to modify roof trim on an addition to make it both easier and he thought it would look better. Which it would except that a future phase of the project involves adding a porch in such a way that the frieze on the addition becomes the casing for the porch beam. The continuity was important to the client to calm that side of the building. In the image, the red over the window is where the contractor wanted to case the window with 1 x 4 thus creating a narrower frieze board. When that line got over to the porch on the left it would have to drop down to case in the porch beam. Not smooth. On the windows above, the casing for the windows is independent and below the frieze which is preferable, however, I was setting the three lower windows as high and large as I could over a countertop to maximize light into a deep room. We were squished also in terms of the roof in order to get it well under the upstairs windows. Especially over the porch area. The contractor's solution would be fine and what I would have designed were it not for the open porch to the right. I found, during the years I worked as a carpenter, that it was easy to concentrate on the task at hand and lose sight of the overall picture. As a designer, sometimes I'll make a foundation more complicated in order to make framing or trim more simple. Or sometimes I'll do things in a more complicated fashion due to an aesthetic historical precedent. (Isn't much of traditional design like that?) Sometimes I will complicate things to make the end result look simple. Sometimes I complicated things just because I can be really really picky.

I found, during the years I worked as a carpenter, that it was easy to concentrate on the task at hand and lose sight of the overall picture. As a designer, sometimes I'll make a foundation more complicated in order to make framing or trim more simple. Or sometimes I'll do things in a more complicated fashion due to an aesthetic historical precedent. (Isn't much of traditional design like that?) Sometimes I will complicate things to make the end result look simple. Sometimes I complicated things just because I can be really really picky.

Then I looked at a larger barn with more "clipped" New England eaves. Need to work on the front windows. Traditional barns often utilized some asymmetry here but more modern barn builders seem to stick rigidly to symmetry. The side windows are not good however. -see last picture. Perhaps two large windows

Then I looked at a larger barn with more "clipped" New England eaves. Need to work on the front windows. Traditional barns often utilized some asymmetry here but more modern barn builders seem to stick rigidly to symmetry. The side windows are not good however. -see last picture. Perhaps two large windows

Here are some photos from a current project. The interior of the exterior walls are all gutted and exposed for new insulation and air sealing. We are not going for a deep energy retrofit here but the end result should cut the energy use significantly. This is an old house with various interventions over the years, some of which we are removing and some we are changing. This is an example of a project where I was hired to help out with some basic design services but every time I showed up on the job, more of the existing was removed and opened up. A moving target in terms of "scope of work". At this point I am just trying to keep up with things on paper and am acting more as a consultant. I suspect when all is said and done, a lot of this isn't going to end up on paper.

Old, very old and new framing

Old, very old and new framing

the Backside of the oldest fireplace now exposed.

the Backside of the oldest fireplace now exposed.

Interesting eave detail -no rake overhang, the crown returns on the horizontal and there is a big ugly box to mount the gutter too

Interesting eave detail -no rake overhang, the crown returns on the horizontal and there is a big ugly box to mount the gutter too

Front door and window detail on the main house

Front door and window detail on the main house

Process is a moving target. It changes based upon so many variables, not the least of which is the client. Lately, I've been thinking about all my past work and how, to some extent each project represents where I was at that point in time but mostly, every project represents the client much more than myself in terms of philosophy, aesthetics, etc. Many decisions are made in every project that are, perhaps, guided be me but are not what I would have done if given Carte Blanche. I regret some of these decisions but it is important to remember that they were not my decisions any more than the project was "my project" If a project strays too far from what I want to be associated with, (it's ugly) it doesn't show up in my portfolio. There are plenty of those out there. Sometimes you see it coming and sometimes not. Every now and then you get a client who really wants to listen to what you have to say and is interested in your philosophy but mostly, you just have to sneak that in when nobody's looking.

I had another comment recently from a builder who wants to build a house that breathes. I started to reply in an email and then decided to put it hereon the blog instead. What we are doing nowadays in the world of high performance homes is based on studying hundreds of thousands of houses built in the last half century that have failed (which includes the majority of 70's and 80's super-insulated and passive solar homes in the northeast) and applying those lessons to building a durable house nowadays. Houses from before that time period that failed for one reason or another are mostly gone and many of those that remain are simple piggy banks for big oil. We put our money in and the oil companies take it out. Simple. (usually, I like simple but...) For the past few decades, builders in the northeast have been living in a vacuum while the northern Europeans and Canadians paid much more attention to how houses fail, learning from them and adapting. Now the conversation is opening up again and we are taking a seat at the table.

I have lived in houses that breath my whole life. It sucks. Aside from the part where you have to give your money to someone else just to not freeze to death in the winter, there is the comfort aspect of things. Houses I have lived in have never been all that comfortable whether in terms of temperature or moisture levels or even wiping mildew off the window sills. Now, with two children, I worry about the air quality and mold issues inherent in my house that breathes. I would rather be able to seal up the house in the winter and be confident that I was breathing fresh Vermont air all the time than have to step outside for a breath of fresh air or open up the doors and windows if I screw up on getting the woodstove going. Six months out of the year, I would still have the choice to open the windows and turn off the HRV.

We do seem to have more summer moisture and humidity problems than we used to but we also have access to more durable and proven materials and building methods. Some builders and architects are taking advantage of this but most are building the same way they did 20 years ago despite all the failures. A house that breathes and has little or no insulation is a barn and If you want to heat it, that means coming to terms with giving your money away. Jesse Thompson says "People breath air through their lungs, not their skin. Why should houses be any different?" If you want your house to breathe, give it a set of lungs.

There are a range of options for doing this from exhaust only bathroom fans and range hoods (simple and cheap but where does the makeup air come from in a very tight house?) to a full-on Heat Recovery Ventilation System or HRV. These are also fairly simple and effective although significantly more expensive but have the added advantages of recovering much of the heat from the outgoing air as well as providing fresh incoming air exactly where you want it. For more information just type "HRV" or "house ventilation" into the search box on Green Building Advisor and start reading.

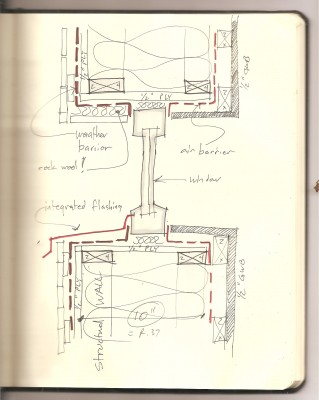

Designing a Super-insulated wall with good drying potential and good air sealing is easy. But the Devil is in the windows. With passive house level construction we want the window to be recessed toward the middle of the opening and the middle of the adjacent insulation layer. This is about thermal bridging and heat loss. An advantage that I've found is that it can potentially simplify the flashing which is certainly a welcome idea. Window and door installation has become increasingly complex over the past decade especially with exterior foam details. (I try to stay away from that) What I'm looking at in this sketch is how flashing for siding can be decoupled from flashing for the window to a great extent. Does the siding even need flashing anymore? Depends on how you do the siding. With some Rain screen siding details, perhaps not! Windows are now coming with really nice integrated sill flashing - you specify the depth when you order. This makes for a much more integrated and seamless system which should have long term durability advantages over what we have been doing up until now. What is missing from this drawing is an exterior layer of rock wool insulation to keep the sheathing warm (not rigid foam !) A more expensive detail and this may be less important when using cellulose than fiberglass insulation but is a detail I would certainly do on my own home. The other option is to use more of a Larsen truss system similar to what Chris Corson is doing in Maine with no exterior sheathing. It is A tough sell around here to leave the insulation protected only by a weather barrier such as Mento plus. The conversation on building science is terribly interesting and seems to be resolving itself towards simplicity as we gain knowledge and experience about what works and what doesn't and develop products and materials based on our increasing knowledge base. Of course, 93% of builders and architects aren't really paying much attention.

Designing a Super-insulated wall with good drying potential and good air sealing is easy. But the Devil is in the windows. With passive house level construction we want the window to be recessed toward the middle of the opening and the middle of the adjacent insulation layer. This is about thermal bridging and heat loss. An advantage that I've found is that it can potentially simplify the flashing which is certainly a welcome idea. Window and door installation has become increasingly complex over the past decade especially with exterior foam details. (I try to stay away from that) What I'm looking at in this sketch is how flashing for siding can be decoupled from flashing for the window to a great extent. Does the siding even need flashing anymore? Depends on how you do the siding. With some Rain screen siding details, perhaps not! Windows are now coming with really nice integrated sill flashing - you specify the depth when you order. This makes for a much more integrated and seamless system which should have long term durability advantages over what we have been doing up until now. What is missing from this drawing is an exterior layer of rock wool insulation to keep the sheathing warm (not rigid foam !) A more expensive detail and this may be less important when using cellulose than fiberglass insulation but is a detail I would certainly do on my own home. The other option is to use more of a Larsen truss system similar to what Chris Corson is doing in Maine with no exterior sheathing. It is A tough sell around here to leave the insulation protected only by a weather barrier such as Mento plus. The conversation on building science is terribly interesting and seems to be resolving itself towards simplicity as we gain knowledge and experience about what works and what doesn't and develop products and materials based on our increasing knowledge base. Of course, 93% of builders and architects aren't really paying much attention.

(would make a good bumper sticker for me except that nobody would get it.) In rural northern New England – the only local I can really speak authoritatively about – there is a dichotomy of class. It may not reflect income or race but it is something I grew up with. The local kids worked in the kitchens and grounds of the summer camps where the “rich kids” came to play for the summer. It is interesting to read “Maine Home and Design” as an architect who has some connection to the world of art and leisure depicted in those homes as well as a connection to the “other” Maine to whom the magazine is totally irrelevant.

I find the dichotomy affects my own work as well as the clients I have worked with. The typical client with a more middle or upper class suburban background (most of my friends and clients) was raised in a largish home on a largish lot where each kid had his or her own bedroom, there were multiple bathrooms, a garage, a family room – standard stuff to most people. Growing up in rural Maine, however, I had friends who lived in un-insulated homes with no plumbing, 12' wide mobile homes etc. For many, the ideal was one of those new 1200 s.f. Modular homes built up in West Paris. Lots of families included multiple generations and semi-temporary guests all under one roof in a big old farmhouse.

After many years of clients coming to Vermont to build a new home and life who find the idea of not having a master bedroom suite, a T/B ratio =/> 1 (toilet to butt ratio) or a garage to house their cars incomprehensible, (Real Vermonters don't have garages?) I find myself questioning what is important to me and the type of projects I can really get my emotions into. My job requires a fair amount of understanding where someone is coming from and what their frame of reference is. Certainly, most people bring their past with them to the table along with what they see on the internet and in magazines. But when I get a client who with similar (old fashioned?) sensibilities and more of a “slow living” attitude and perspective or at least, a willingness to question their values, it is refreshing.

In designing with a set of priorities to reflect this attitude I think about more seasonal living with the idea of hunkering down close to the woodstove during the colder months, cooking lots of fabulous meals and hosting smaller gatherings of friends and family. In the warmer months, life can expand outward with larger parties in the barn, screened porches become additional living space and sleeping quarters. In my own family's case, the 900 square feet of wood stove heated living space expands to include a screened in porch where we play and eat meals, the barn where I have a desk set up to work and where we have parties and guests have a comfy bed. Plus there is always the fern house and lots of room for tenting in the meadow. Sometimes it is good to tour old houses or even just spend some time in old Sears catalog home books to see what used to be important to people and think about how we say we want to live with a more critical eye and a different perspective.

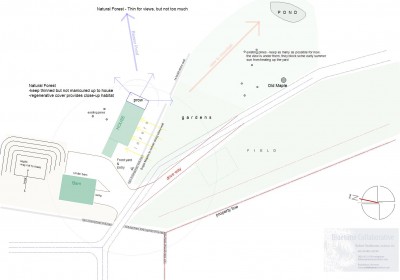

Sort ofThis is a schematic design for a local project I'm working on where I am doing master planning up front. See this post. After meeting with Gary MaCarthur to look at the whole site and master plan in terms of solar potential - the owners may, at least initially be "off the grid" - it was clear that the best locations for the house and barn were not so great for photovoltaics. Gary, like many other folks who design and install PV, like a clean simple installation, Ideally on the steeply pitched roof of a shed where the equipment can be housed. "a Power House". I knew the owners wanted to be able to spend weekends on the site year round and be comfortable and we had discussed building the barn first and finishing off the upstairs. Not a great solution unless you are prepared to build a fairly expensive barn as opposed to a pole barn for equipment and animals. Gary, upon listening to the master plan, long term build-out goals, suggested a cottage instead which could eventually become a guest house but in the meantime would serve as compact living quarters, the power house and storage for a tractor and whatever things get left here on a more permanent basis initially. being relatively small, a cottage could fit nicely into the overall site plan in a location ideal for photovoltaic panels.

As usual lately, I'm trying for the holy grail on this one and I hope the clients like the ideas. Holy Grail = Competitive cost Passive house priciples of low energy use, durable design and good building science local materials wherever possible and minimal environmental impact of materials Logical construction methods – nothing complicated or fancy Simple modern design – Scandinavian-ish? Clues from tradition but not a slave to it. - No Anachronism - use what works and eliminate frippery Texture and light and air Shadow and light. Intimately tied to the land. Seasonally adaptive and responsive Low maintenance – no or minimal exterior paint, stain , varnish – weathering materials and durable materials Emotionally uplifting space Proportion and grace.

Specifically to this project the long design seems to work best in terms of what we want to do with the site, the available roof for solar, the idea of layering, keeping the roof sheltering and low at the eave, build part now/part later if needed to get power set up, the gardeners cottage / gatehouse idea, overall simplicity, steep roof (Gary says to max winter gains) etc. I was also looking at cladding materials in more of a fabric sense with varying degrees of transparency which seems very Japanese and works very well for how I design wall systems.

Here is the initial sketch from my sketchbook:

It's not often I get to do this. I am usually called in when it is too late to have much input into overall site design on a rural project. I am a scholar of historic farm and homestead planning and I am always acutely aware of the relationships between the various elements of the site whether natural, man-made, Solar, weather, history (stone walls and old roads, etc - very important in New England) and the buildings that are located to be a part of the landscape (or not as is often the case) Design often starts with floor plans but is so much richer in the long run when the site is considered with as much rigor and intensity as the floor plans. How a home "lives" is very much a function of how the land outside the walls of the house "lives" from the point outside the front door to the yards to the property lines to the town, region, state...

It's not often I get to do this. I am usually called in when it is too late to have much input into overall site design on a rural project. I am a scholar of historic farm and homestead planning and I am always acutely aware of the relationships between the various elements of the site whether natural, man-made, Solar, weather, history (stone walls and old roads, etc - very important in New England) and the buildings that are located to be a part of the landscape (or not as is often the case) Design often starts with floor plans but is so much richer in the long run when the site is considered with as much rigor and intensity as the floor plans. How a home "lives" is very much a function of how the land outside the walls of the house "lives" from the point outside the front door to the yards to the property lines to the town, region, state...

I often need to spend minimal time - 10 to 20 hours at my hourly rate - to do a simple master planning/feasibility study to explore what can be done to an existing house and if it's worth it. This process includes measuring existing conditions as much as is needed, photos, a thorough initial client meeting, thinking, sketching, some schematic design, modeling, more thinking, writing lists and generally trying to pare down the simplest solution to the client's goals. The result is a .pdf file which attempts to get all this down in a clear format which can be given to a builder for feedback and a VERY rough costing on the various parts and options. I have been assured by other architects that I am ridiculously fast at this in terms of total time spent. Projects often don't progress past this stage as clients realize that it would cost more to achieve what they want than they are able to spend. Or the project gets pared down at this early stage. It is a very useful exercise in saving money by spending some on the architect up front. It seems to be a good graphic way to quickly get a handle on the whole project without committing much in terms of $ from the client or time from me. Here are some examples of three recent projects.

Some images from the model. Of course I don't think the clients can afford it but it's a good starting point. This is a one car garage with a studio space above it, a rear yard screen porch and a mudroom connecting all these. We can treat the addition as a separate unit from the existing house itself by building it to passive house standards and heating it (and cooling it) with a simple mini split heat pump. or we could ignore the cooling aspect and use a very small amount of electric heat.

Apparently, although I never got an email, I am now a Certified Passive House Designer!!

What is Passive House ?

- The passive house standard represents the highest level of energy efficiency and “green building”. - The passive house standard is where state and municipality energy codes are headed. - Public housing groups such as Habitat for Humanity and regional housing authorities and land trusts are starting to require new housing units to be built to the passive house standard as these groups tend to prioritize overall cost of ownership over initial cost of construction. - The roots of Passive House trace back to the 1970s, when the concepts of superinsulation and passive solar management techniques were developed in the United States and Canada. - More than 25,000 buildings have been built to the Passive House standard in Europe. The standard is especially common in multi-family housing where it often makes little financial sense not to build to this level of energy efficiency.

Concept “Maximize your gains, minimize your losses”. These are the basic tenets of the Passive House approach. A Passive House project maximizes the energy efficiency of the basic building components inherent in all buildings; roof, walls, windows, floors and the utility systems: electrical, plumbing & mechanical. By minimizing a building's energy losses, the mechanical system is not called to replenish the losses nearly as frequently. This saves resources, operational costs and global warming related pollution. Unlike any other structures, Passive House buildings maintain occupant comfort for more hours of the year without the need for mechanical temperature conditioning of the indoor air. The opposite has been the norm in this country where we have a history of inexpensive fuel and construction techniques with little consideration for energy losses through thermal bridging, air-infiltration, and inadequate levels of insulation.

Passive House is both a building energy performance standard and a set of design and construction principles used to achieve that standard. The Passive House standard is the most stringent building energy standard in the world The Passive House approach focuses on the following:

Strategic Design and Planning: Passive House projects are carefully modeled and evaluated for efficiency at the design stage. Certified Passive House Consultants are trained to use the Passive House Planning Package (PHPP), a tool that allows designers to test “what-if” scenarios before construction begins. They are also trained to use other software tools to identify and address potential thermal bridges and moisture issues at the design stage. Specific Climate, Siting and Sizing: Passive House design uses detailed, specific annual weather data in modeling a structure’s performance. Orientation of the windows can maximize or minimize solar gain and shading. Passive House theory leans towards minimizing the surface area to interior volume ratio, favoring an efficient shape to minimize energy losses. Super-Insulated, Air-Tight Envelope (But Diffusion Open): To keep the heating/cooling in, wall assemblies require greater insulation values to “stop the conditioned air” from leaving. Walls are typically much thicker than today’s standard construction. Passive House takes great care in designing, constructing and testing the envelope for an industry-leading control of air leakage. Blower door testing is a mandatory technique in assuring high performance. Walls are designed to be virtually air tight, while allowing water vapor to dry out. “If moisture gets into the wall, how does it dry out before damage can occur?” is a fundamental tenet of modern building science addressed in Passive House design. Wall assemblies are analyzed to allow for proper water and moisture management to make a long lasting and an exceptionally healthy building. Thermal Bridge-Free Detailing: Breaks in the insulation layer usually caused by structural elements and utility penetrations in the building envelope create a “thermal bridge,” allowing undesirable exterior temperatures to migrate to and “un-do” expensive interior conditioned air and creating colder interior surfaces that encourage the growth of mold. Passive House design attempts to minimize thermal bridges via progressive mindful architectural detailing. Advanced Windows and Doors: Historically these items are the weak link of a building’s envelope and thermal defense system. Passive House places significant emphasis on specifying high performance windows and doors to address concern. To meet the high performance needs of various climate zones, windows must meet strict performance standards regarding: component insulation, air tightness, installation and solar heat gain values. Energy Recovery Ventilation: The “lungs” of a Passive House come from a heat (or energy) recovery ventilator (HRV/ERV). It provides a constant supply of tempered, filtered fresh air 24/7 and saves money by recycling the indoor energy that is typically found in exhaust air. The heat from outgoing stale air is transferred to the unconditioned incoming fresh air, while it is being filtered. It provides a huge upgrade in indoor air quality and consistent comfort, especially for people sensitive to material off-gassing, allergies and other air-borne irritants. HRV's are fast becoming standard equipment in all new houses in Vermont. Heating: One of the best benefits to implementing Passive House design is the high performance shell and extremely low annual energy demand. This allows owners to save on operational costs as they can now significantly downsize a building’s mechanical system. Passive solar gains, plus heat from occupants and appliances supply most of the needed heat. Radiant floor, baseboard, or forced hot air heating systems are unnecessary! Alternative Energy: Considering alternative energy systems on your project? Building to meet the Passive House Standard is the smartest starting point. The significant reduction in energy use, allows alternative energy to power a greater percentage of a buildings demands. Likewise smaller demand equates to smaller and more affordable alternative energy systems providing higher cost-benefit value. Passive House design puts a project within reach for achieving true “Net Zero” performance (the building generates as much energy as it consumes over the course of a year), making use of alternative energy systems smaller thus more affordable and attainable.

Dreaming in ArchitectureI have noted before that I have probably spent more time thinking about design in my adult life than most people have spent sleeping. In this post I shall one-up myself. Sometimes I dream-design. In a dream a few days ago there were some houses moved onto our property that had been built by my late father-in-law and we had inherited them. It was in the middle of the winter and the property bore no relation to our own and my father-in-law didn't build houses and there was other strange dream stuff such as the two elderly Asian women sitting high up in a window of one of the houses eating and the sink was full of dishes that should have been frozen in another house. You get the picture. In one house, there was a specific arrangement of the stairs to the very long kitchen table which set me off into that place in my head where I design things – It seems that whether I'm conscious or not has little to do with it. I started exploring the design and pinning things down on a very personal thesis of some things I really would like to explore in how I would like to live in a house in Vermont.

The idea of a very long kitchen table that was where everything happens formed the basis of my exploration. An important part of the thinking came from a recent photo I had seen in a magazine with a hearth room off the kitchen where the ceilings were low, windows minimal and set in deep walls, books, mattresses, comfy chairs, a stone floor, and lighting only for reading. It is a perfect space for reading in the winter evenings. It is very “Slow Living” Who needs a living room? An advantage of designing while I am dreaming is that my ideas come out with greater clarity. When I wake up and sketch out my ideas I may find that none of them work very well in that they ignore some practical aspects of form and function. This design, however, identifies some issues that I will need to think about and develop. It probably isn't very marketable as it comes from so deep within my own self but it may be interesting to others in terms of thinking about how design can respond on a very deeply emotional and personal level that goes far beyond searching for the perfect floor plan.

As I have mentioned before, much of my work is for people who would never have gone to an architect in the first place, thinking that they could never afford it. Designing a custom home for someone is an incredibly complex endeavor. You can buy a set of plans relatively cheaply that may go 75% of the way towards fulfilling your needs and end up with a decent house. Most people go this route. However, some of my best work to date has been for people who are more concerned with money and value. I have been hired by clients to say “no, you can’t afford it” when they lose focus in the process of building a home and start to make a decision or series of decisions that would blow the budget. A good architect should be able to save a client at least the cost of architectural services if that is one of the stated goals. If you have $250,000 to spend on a house you can buy a plan and build a house that is worth $250,00 or you can spend $20,000 on an architect and build a house for $230,000 that gets you a better looking house with a more efficient and flexible floor plan and nicer spaces that fit your lifestyle more comfortably, a house that costs less to maintain over the longer term. Notice that I keep saying “good architect”. As with any profession there is a wide range of talent and specialties. Always ask for and check references. Find an architect and a builder who you are comfortable with. You need to develop a good relationship with these folks. They’re not just there to sell you something.

Of course if you have lots and lots of money, maybe you don't need an architect. Many problems can be solved by throwing more money at them. Perhaps a not-so great-floor plan can be solved by increasing the size of the building. If it starts looking too big you can add jigs and jogs and gratuitous dormers and gables to lessen the visual impact. Perhaps a high heating bill doesn't bother you so why bother with energy modeling and value engineering? Perhaps you are not planning on spending a lot of time in the new home so certain things are simply less important. If your caretaker discovers leaking, rot and mold 6 years down the road there are folks who are perfectly willing to deal with that too.

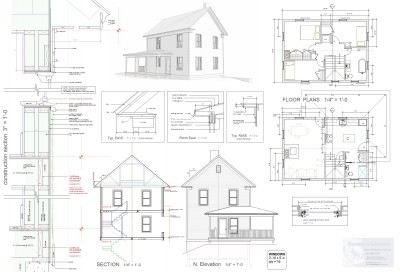

Here is an example of a basic one-page-wonder construction drawing for a simple house. Not all the information is here to build a house but an expert builder can fill in missing details. For example, I put the stairs in the section with a very basic level of detail to make sure they work and meet code, however, I did not detail anything further than that. The stairs could be built in a very modern way with cable railings or very old fashioned with spindle ballusters and a newell posts. I concentrated on the overall aesthetic, proper Greek Revival details for the location and good building science practices with a very detailed double stud wall section from foundation to roof.

I have competed the Passive House consultant/designer training and am almost ready to take the exam on Friday of this week. (eek!) Training consisted of 2 three-day sessions in Boston with instructors from Passive House Academy. There were 8 other people in my class including 5 architects, two people from European window companies and a person from an air exchanger company and I have to say that despite the difficulty and intensity of the material covered, we had fun. The instructors were Irish so, in the same way that I slip back into a Maine accent when I am talking to someone from Maine, I found myself speaking and even thinking with that lovely Irish flow. That lasted about a day and was somewhat annoying.

I have competed the Passive House consultant/designer training and am almost ready to take the exam on Friday of this week. (eek!) Training consisted of 2 three-day sessions in Boston with instructors from Passive House Academy. There were 8 other people in my class including 5 architects, two people from European window companies and a person from an air exchanger company and I have to say that despite the difficulty and intensity of the material covered, we had fun. The instructors were Irish so, in the same way that I slip back into a Maine accent when I am talking to someone from Maine, I found myself speaking and even thinking with that lovely Irish flow. That lasted about a day and was somewhat annoying.

The course and the training is relatively new and evolving. The content of the course is all about creating super low energy use buildings using highly vetted building science. The concept is based on these 5 fundamental principles:

-Very high levels of insulation -Avoiding thermal bridges -Using high performance (and very nice and very expensive) windows and doors -Airtight construction (lots of detailing and testing to insure air-tightness) -Controlled mechanical ventilation with heat-recovery

Example of Structural Steel with no thermal bridging

Example of Structural Steel with no thermal bridging

This is all familiar stuff to any builder or architect who is paying attention these days but Passive house goes beyond the current codes to where codes will be in 10 to 20 years. This is passive solar design from the 70's brought to the highest levels. It is no longer experimental but based on sound physics, a huge data base of existing projects, an understanding of moisture and air quality issues. It is also very much based on simplification. We have a huge understanding of how buildings work and how they fail so Passive House is all about using that knowledge to create buildings that succeed. For a great primer on Building science check out the Summer 2012 issue of Fine Homebuilding which you may still be able to pick up on newstands. There is an article by Kevin Ireton entitled “The Trouble With Building Science.

The economics of building to the Passive House standard are very persuasive. So persuasive that housing groups around this country including Habitat for Humanity and public housing developers are taking notice. They already took notice in Europe of course and are building many housing projects to using Passive House principles. Schools are a particularly important application of Passive House design because of air quality in particular. When you add long term operating and maintenance costs, energy costs, decreased liability issues etc. to the initial building costs, it is hard to imagine building any other way. In Europe the banks are taking notice of this as well in terms of favorable lending rates.

A big selling point is air quality and the durability of buildings. The current state of building in the U.S. is fairly dismal. Even most building and energy codes are based on a rather half-assed interpretations of building science. We have been creating buildings that are too complicated, cost too much to maintain, have air quality issues due to a number of factors often involving mold and other moisture and air quality related problems.

So the six days were spent looking at proven projects including many retrofits, studying and understanding details and products as well as overall design approach (very 70's solar) understanding the economic issues, covering mechanical systems, understanding how buildings succeed or fail, and diving into the basic physics of it all.

An example would be: If you add x amount of insulation or upgrade the windows to a more expensive, better performing model, how much less heat will you need to pump into the building in the winter and cooling in the summer thereby saving heating and cooling costs? And not only that but can you get the heating and cooling needs low enough so that you can spend less money up front on a simpler and cheaper heating system? [note: with Passive House design, radiators -if you even need them -don't need to be under windows] And are surface temperatures in the room such that moisture will not condense on cooler surfaces in corners due to thermal bridging? - something that becomes hugely important when you super-insulate.

I really appreciate the whole concept of doing it right the first time as well as the focus on simplification. (Anyone who has looked into the mechanical room of a building built in the past thirty years should understand the need for simplification) I also appreciate that Passive House goes into a deeper level of common sense “green” than net-zero, LEED, Energy Star and all other certification type programs – some of which are rather laughable. I will repeat myself from a previous blog entry before I started this whole Passive House thing: “If the Shakers were still building, they would be building passive Houses!”