I have started working on the Perry Road porches. Freezing my butt off and that sort of thing. But it is fun to do a bit of carpentry again. I will post pics here as things progress.-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

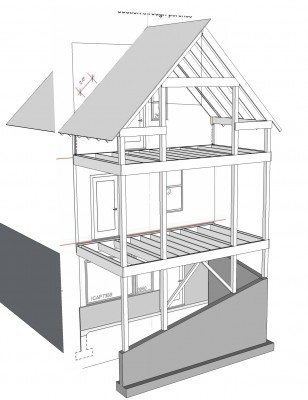

This is yesterdays (1-4) photo. I spent today finishing up details before metal roofing goes on. The whole thing is solid and straight. One of the things I like about carpentry is the problem solving aspect. I like to figure out the whole enough to know I won't get into trouble on a detail later on. There is an aspect of improvisation to it. When I built my fern house, there were no drawings. I sketched out enough of the whole to understand that the details would be easily solved as I went along - and they were. I suppose this is not very architecty of me but it works out fine. I think this is what separates good carpenters from the rest - the ability to look ahead and work with all levels from the whole to the minute details simultaneously. I have often seen carpenters do what seems easy or logical at the moment only to get boxed into a bad detail resolution later on because of the inability to conceptualize the whole. Much of my detailing as an architect is just enough to guide a builder along a path without them getting boxed in but allowing room for improvisation and improvement.

-

-

This is yesterdays (1-4) photo. I spent today finishing up details before metal roofing goes on. The whole thing is solid and straight. One of the things I like about carpentry is the problem solving aspect. I like to figure out the whole enough to know I won't get into trouble on a detail later on. There is an aspect of improvisation to it. When I built my fern house, there were no drawings. I sketched out enough of the whole to understand that the details would be easily solved as I went along - and they were. I suppose this is not very architecty of me but it works out fine. I think this is what separates good carpenters from the rest - the ability to look ahead and work with all levels from the whole to the minute details simultaneously. I have often seen carpenters do what seems easy or logical at the moment only to get boxed into a bad detail resolution later on because of the inability to conceptualize the whole. Much of my detailing as an architect is just enough to guide a builder along a path without them getting boxed in but allowing room for improvisation and improvement.

-

-

We got the roofing on last week in time for the big snowstorm

-

We got the roofing on last week in time for the big snowstorm

Budget lessons for the architect (me)

Here is an interesting lesson to learn if I can figure out what it is. Perhaps writing this blog entry will help.I tend to attract the sort of client who wants a 2500 square foot house with porches, hardwood flooring, granite countertops and an attached garage and wants it for $275 K. If they don't flee the office in disgust when I tell them A: can't be done and B: my fees would definitely be more than $3000. (There will of course be someone who will “say” they can) What has happened too often to ignore in the past several years is that clients have come to me with a set of parameters (we architects refer to this as a program) The program consists of needs, wants, site and zoning issues, budget etc. Usually the budget requires a rethinking of needs vs wants and this is where things can get sticky. As I mentioned above, there will always be someone who will tell them they can have it all (meaning: let's wing it) and some clients will seek them out. A few years later when I see the project completed without me it is clear that either the budget was much more “flexible” than it was when they originally came to me or the “needs” list was pared down much more than what I was able to accomplish with them. I know I am not the best salesman, hoping instead that my obvious experience, references and air of quiet competence will engender trust (insert emoticon here) (real men don't use emoticons) There have been times when I have thought of a great solution to a design problem but scrapped it because it was a budget buster only to find out later when the clients went to another architect who came up with the same idea and “sold” it to the client. Discouraging. Perhaps the lesson is that I should take things a bit less personally and realize that other people's idea of budget is more flexible. Of course, I am often the second architect on a project because the first architect designed something too expensive to build...

Architectural services are basically "Advice"

File this under “Education of an Architect”People hire me for my professional advice. This may take the form of helping them design a house or do some master planning or a simple addition. It all boils down to advice. Some people try to hire me for drafting but I try to make it clear that if I see something that isn't working or is unnecessarily complicated or un-buildable or even just plain stupid, I'm not going to ignore it. There are often times in the process when the client and I disagree and depending on how important the issue is, I'll push back. If the issue is not so important such as a siding material or color I'll say my piece for the record and then lay off. If the issue is a bigger one and involves the client basically shooting themselves in the foot in terms of budget or previously stated design/function goals or sustainability issues or if it would result in something so ugly that I wouldn't want my name associated then I'll push harder but only up to a point – I'm not much of one for a fight and I'm not the sort who comes into a project with a slick attitude of “I know what's best”. There are times when I've gotten kicked off a job or removed myself because of such issues. Things that had I caved in on would have come back to haunt me later. The architect is an easy entity to blame for design decisions when all is said and done even if there is a good paper trail showing the architect's protestations. Sometimes clients state a set of expectations up front involving budget, design goals, functional requirements and time frame that represent an unsolvable equation. This is where a slick architect or builder has the initial advantage over me. If I am unsuccessful at helping the client re-define these parameters, (sales and education) then I walk. In the past I may have been naïve enough to go forward with the project anyway but when proven right, I got the blame. Sometimes, I see completed projects that I turned down and another architect was hired where it is obvious that the other architect was a better salesman and educator than I and the compromises that I recognized would be necessary are apparent in the final product. Sometimes, I don't take a job and hear later though the grapevine about how the clients fought with the architect and everyone came out with sore feelings and tarnished reputations. The projects pictured on my website (I really need to get out and photograph a bunch of recent projects) never represent what I would have done on a given site and with a similar set of design parameters but instead represent advice – some taken, some not.

A Good Architect-or-Why you should hire one.

I am bringing this post forward because, well, because I like it. As I have mentioned before, much of my work is for people who would never have gone to an architect in the first place, thinking that they could never afford it. Designing a custom home for someone is an incredibly complex endeavor. You can buy a set of plans relatively cheaply that may go 75% of the way towards fulfilling your needs and end up with a descent house. Most people go this route. However, some of my best work to date has been for people who are more concerned with money and value. I have been hired by clients to say “no, you can’t afford it” when they lose focus in the process of building a home and start to make a decision or series of decisions that would blow the budget. A good architect should be able to save a client at least the cost of architectural services if that is one of the stated goals. If you have $250,000 to spend on a house you can buy a plan and build a house that is worth $250,00 or you can spend $20,000 on an architect and build a house for $230,000 that gets you a better looking house with a more efficient and flexible floor plan and nicer spaces that fit your lifestyle more comfortably, a house that costs less to maintain over the longer term. Notice that I keep saying “good architect”. As with any profession there is a wide range of talent and specialties. Always ask for and check references. Find an architect and a builder who you are comfortable with. You need to develop a good relationship with these folks. They’re not just there to sell you something.

This also from an older post: I see many houses around here that would have benefited from some professional design help. It seems that people like to spend more money than they need to . These houses look complicated (if it looks complex then it is expensive) and yet they are obviously intended to be low cost housing. Not many people (or banks) “get” that spending money on an architect or designer up front can save them much more money in the months to follow during construction. Perhaps it is similar to solar hot water systems. Spend 5k to 7k up front and it takes 5 years or so before it is paid off in savings and then it starts saving money. It’s like putting and extra $50 in the bank every month. That’s an extra $6000 dollars over the next 10 years not counting for interest and certainly not counting for rising oil, gas or electricity costs. There was a picture in this month’s “National Geographic” showing a Chinese subdivision from above. Many of the houses had solar hot water systems on the roof. They must be smarter than us.

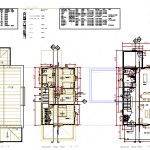

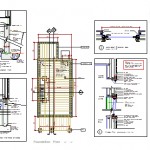

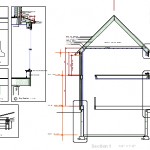

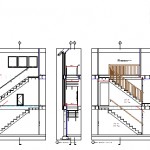

Typical Simple Construction Drawing Set

This represents a typical Construction Drawing set for a simple house minus a site plan. It represents a bit over 100 hours of labor. Thought y'all might be interested. A more complete set would have framing on a separate sheet, Interior elevations at least of the kitchen and bathrooms, a site plan, Materials schedules usually called out on the floor plans, and separate electrical plans.

How to become an architect

People often tell me they took a drafting class in high school and thought about becoming an architect. I took a drafting class in high school and thought about becoming an architect. I suspect that few people have in idea of what it takes in terms of the whole process. First there is admission to a school of architecture. These tend to be highly competitive. My school accepted fewer than one in seven applicants the year I was accepted with admission to the rest of the school being much easier. Artistic talent, leadership skills and life experience were important. High school drafting class counted for nothing. The first year of architecture school is a bit like hazing and typically, about half drop out. Then you are in school (think massive debt) for 5 years at a minimum. Five years gets you a professional degree called a Barch which is a bit more than a regular bachelors but less than a masters. This degree is being phased out because it is becoming impractical to cram all the course work into five years. ( graduated with 181 credits) The new norm seems to be a 4 year degree resulting in a liberal arts type bachelors degree and an additional 2 to 3 years for a Masters degree in architecture.

Then comes post graduation internship (if you are lucky enough to get a position with an architecture firm) Working full time, the requirements for this can theoretically be met in about three years. I have heard that the average internship lasts 7 years but this seems to be a dirty little secret in the industry. My own internship was about 5 years worth of time spread over a much longer period of time because I spent so much time working as a carpenter. It took five years of actual internship because there are a specific set of criteria that must be met to satisfy the internship requirements which are often hard to accomplish without spending some time working in a large urban firm where a regular internship program is in place. Many graduates who go to work in larger firms with salaried positions never get around to taking the qualification exams to become licensed architects. They may not need the license for their job and it can be hard to study when you go home in the evening to a busy family and life.

The Exam(s) - Nine of them when I was becoming an architect. Nine exams which represented over $1000 in fees plus all the study materials which is a whole separate industry. In the old days the exams took place all at once over a 4 day period where you were locked in a room with a drafting table. Now you stare at a computer screen at a cubicle in a small room with flickering florescent lights overhead. (headache)

So, the whole process takes a minimum of 8 years but averages a lot longer. Probably not worth it from an accountant's point of view when looking at the yearly salary data that comes out courtesy of the American Institute of Architects. Then when you finally have license in hand and can legally call yourself an architect there are all the yearly fees and continuing education requirements that must be met to maintain the license. If you lapse on any of these you are not allowed to cannot continue to call yourself an architect.

Phew!

Charlotte and Papa Art

Know When to Run

My architect colleagues will do some nodding here.Sometimes you have to know when to run screaming from a project or risk losing your shirt to someone who probably makes six times your income. -If I client is in a hurry, step away -If a client refuses to divulge budget numbers, back away -If a client has unrealistic expectations and refuses to listen to reason, turn and start walking -If a client wants something for free run for your life! The mistake I have made in the past is thinking I can change someone. If this sounds like the stereotypical doomed personal relationship then BINGO. I am limited in my abilities to educate a potential or new client as to the architectural process and rely on references in the form of previous clients and builders (I always give out a list) If after all this, it is clear that the client hears what they want to hear and nothing more or less than it is time to exit stage left. An example: A few years ago I was hired to do an addition to an old Vermont cape. The addition was to have a large family room, two studies, a bedroom suite with closets and bathroom, a utility room, a porch etc etc. This is a LOT of square footage. I found that I could make a floor plan that made them happy but the resulting massing and scale was far off no matter what I did. I got fired from the job and lost my shirt to someone who can not only afford a second home in Vermont but can afford to renovate and add on. Mental note: future Woe-Is-Me post – why didn't I become a New York architect so I could afford to live in Vermont. In retrospect, I realized that what they were looking for visually was irreconcilable with what they wanted for a program (the floor plan spaces) The addition was to replace a small shed ell which was quite cute and a good match for the old cape and my job was to make the new addition just as small and cute despite containing 4x the space. Impossible. There will always be someone else who will tell them they can do it. Either an architect or designer who is a better salesperson than me and will do fanciful renderings with lots of flowers that make it look okay or a builder who will say “lets just figure it out as we go” and exude confidence all over the place. Yuck. I must assume they found such a person.

Step Two in Design Process

Make that a Barn/Studio Addition

Brattleboro Garage/Studio Addition

A video of a current project - additions to a Brattleboro House

What you can get for What you will pay

You get what you pay for. This is a primer on what you can choose from for architectural design services and most of my projects fall into one of these three categories. 1. I will often do very small consulting jobs on an hourly basis. These are usually brainstorming sessions, structural consults, maybe a simple photoshopped rendering showing what something may look like without hard construction drawings. I enjoy these jobs but tend to lose money on them when I put more time and effort into it than I can reasonably bill for.

2. Most of my addition/renovation and new house jobs are of the second category of basic design services. This is what you get for 6 – 10 % of construction cost from most architects. We start with a basic analysis of needs/desires/budget and enter a process of design (which is lots of fun) there is usually extensive use of sketchup modeling early on. These projects are tough on me as an architect because there isn't time in the budget to explore all options and really flesh out all the possibilities in a scheme. I go into the finished project and see lots of little things that could have happened with more rigorous design. Missed opportunities, changes from the drawings for the worse etc. I often see changes that were due to the builder saying “it's easier to do it this way” without understanding the ramifications either aesthetically or structurally or my personal fav Simplifying the framing in a way that makes finish work more complicated later. At this level I try to get all the big things right and rely heavily on the builder to make good detail decisions. I try to build a lot of flexibility into the design so if, for instance, the concrete sub screws up and pours a wall wrong, (often happens) the plan can adapt. I have been fortunate to have worked with many very good builders. I tend to lose money on these projects as well because I am a perfectionist.

3. At 10 to 15% you get into full bid services and/or construction administration. This is the fun stuff that I rarely get to do, mostly due to where I live and the type of clientele I attract. The design process is as thorough as it needs to be. Subcontractors are utilized in the design process in a more integrated fashion - lighting, kitchen, interiors, landscaping, structural etc. Less is left to the discretion of the builder. This is where I would design the built-ins rather than just leaving room for them as in the second category. We more fully explore material and finish options, appliances and lighting, analyze methods of construction and perform energy modeling. This is the arena for clients who, regardless of budget, understand the value in such rigorous design. These are often people have have built a house before and want to do it right the second time around and are willing to forgo a few luxury items (the standard granite countertop argument for those in the industry) in the budget to pay for full architectural services. This is the standard level of service for many larger and more established firms where there is often an in-house team of experts working on every project. This is also the standard for non-residential projects.

I seem to usually have a mix of the first two project types on my desk at any given time and every few years the third type comes along. Hopefully in the future I will be able to focus more on full service projects.

More about design

After about 8 years of post secondary education, a number of years working for other architects and a decade of running my own design firm with over 100 projects to my credit, I am starting to become a good designer. It is not that I am so un-talented that it took me so long and so much effort to reach this point. It is more a recognition of the standard I hold myself to. See my previous post "What Architects Don't Know". There is a certain amount of frustration when I see ads for local building firms offering design services or even architectural design (illegal) and realize that most people think of design as not much more than a floor plan or drafting. I've always been a good drafter but drafting is just a tool in my toolkit to get the job done, not an end in itself as some hand-drafting cermudgeons seem to view it. (more on that later) Floor plans whether for a new home or other project take more skill, talent and experience but are also a small part of the whole picture. I am often in a situation where I make a simple move on paper that will save the clients thousands of dollars and save the builder a headache during construction and no one but me will ever know it. Thus this blog. It allows me to pat myself on the back a little bit once in a while.

What architects don't know

Architecture is one of those professions where the more you know the more you know you don't know. Many architects don't know this. There are some who “float” and others who are in a constant state of continuing education. I am reminded of this by the large number of architects who state on their websites “We have always been green” but then you look at their projects with a trained eye and see otherwise. Geothermal heating or solar Photovoltaics on a house with 2 x 6 walls, probably insulated with fiberglass batts is an infraction I commonly see. Those architects who read this and don't see the hyppocracy in this example would be the example of “floaters”

Greek Revival Addition to a Vermont Farmhouse

The original house is a fairly new addition to a huge old horse barn. The addition to the addition seeks to correct a number of plan layout and massing issues. The first addition has vinyl siding and poorly proportioned trim and windows which we are addressing.

here it is on YouTube

here it is on YouTube

Greek revival is a bit tricky. There are definite sets of rules about proportions and scale relating to the overall as well as the minute details of trim. Most modern quasi-Greek Revival houses whether architect designed or ticky tacky houses in a former cow pasture ignore these rules and it shows. This is probably an example of ignorance is bliss. Most people look at them and say "oh how lovely" Having studies this sort of thing, I see what's wrong. In reality the style is a copy of an interpretation. Something gets lost in each translation. If you are going to do it at least learn the rules of the game. This model helps me see if I got certain things right or if it may not be possible.

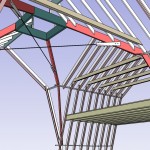

Cross Gambrel

Here is a pic of a house I helped with the structure of. It is quite large and the folks wanted a cross gambrel roof which makes for an interesting structure from an engineering standpoint. Here is an image from the model showing the cross ties pulling the whole thing together.

Here is an image from the model showing the cross ties pulling the whole thing together.

The house kinda looks like the victim of a mudslide but is also rather cool.

The house kinda looks like the victim of a mudslide but is also rather cool.

A client's addition/renovation process blog

http://musingsfromdave.blogspot.com/Here is a process blog from some folks I helped to design an addition for last winter. It was the sort of project where having an architect payed off (if I remember some of the early schemes they came to me with). We were able to phase the project, and with the help of some very thorough pricing by the contractor, make some big decisions before starting construction. The original house was not unlike my own in size - bigger kitchen and only one bedroom though. They wanted a sunny spot to soak up morning sunshine. I gave them four and labeled them as such on the plans.

Vermont Mod Farmhouse update

Here are some photos from a recent site visit to the "Vermont Mod Farmhouse" porches and garage are not built yet but from inside you can start to feel the spaces. This project was a good example of what it's all about for me: light, spatial dynamics, simplicity of form and detailing, a much higher level of plan function than the average house, views, night-vs-day perceptions, modern super-insulation and construction materials and methods, all while maintaining a sense of the familiar. 2240 s.f. plus partially finished walk-out basement, 4 bedrooms.

facade redesign

This is a simple project I did entirely in Photoshop after a site visit to take some photos and talk to the owner. The original house needs updating for a number of reasons. Most of what it needs is rather straightforward and shouldn't require an architect. Originally, you entered the door on the ground floor and immediately went up a narrow set of stairs into the living room. I sketched in a vestibule/mudroom to improve the function and experience of entry. The upper wrap-around porch is mostly rotten and unused so I removed it from the image, reconfigured windows and siding and rendered it in a semi-photorealistic way. In locations without stringent building permit applications this is often enough to take to a builder and get started.